History and Mystery!

Aquilegia saximontana

The case of the delayed avatar

Why is the Rocky Mountain Chapter's newsletter called "Saximontana"?

Taken from the September 2020 Saximontana newsletter.

The article explores the history and mystery surrounding Aquilegia saximontana, a rare alpine columbine. It details the plant’s unique characteristics and its significance to the Rocky Mountain Chapter of the North American Rock Garden Society (RMC-NARGS). The narrative traces the chapter’s logo’s origin, which features the plant, and recounts the discovery and naming of Aquilegia saximontana by early botanists. The article also discusses other related Aquilegia species.

Douglas County, Colorado garden

by Panayoti Kelaidis

I imagine most every member of the Rocky Mountain Chapter (RMC) has admired the oval logo featuring Aquilegia saximontana, but I suspect rather few of us realize that this logo and flower have a bit of history that I don’t believe has ever been recorded. Now is probably as good a time as any to share the story. The logo was designed by Carolyn Crawford Jennings, an extraordinarily talented botanical illustrator who lives in Louisville with her husband Bill. It was created not long after the club hosted the first of what may soon be seven annual General Meetings of North American Rock Garden Society (NARGS). Aquilegia saximontana has been featured on the masthead for the better part of four decades.

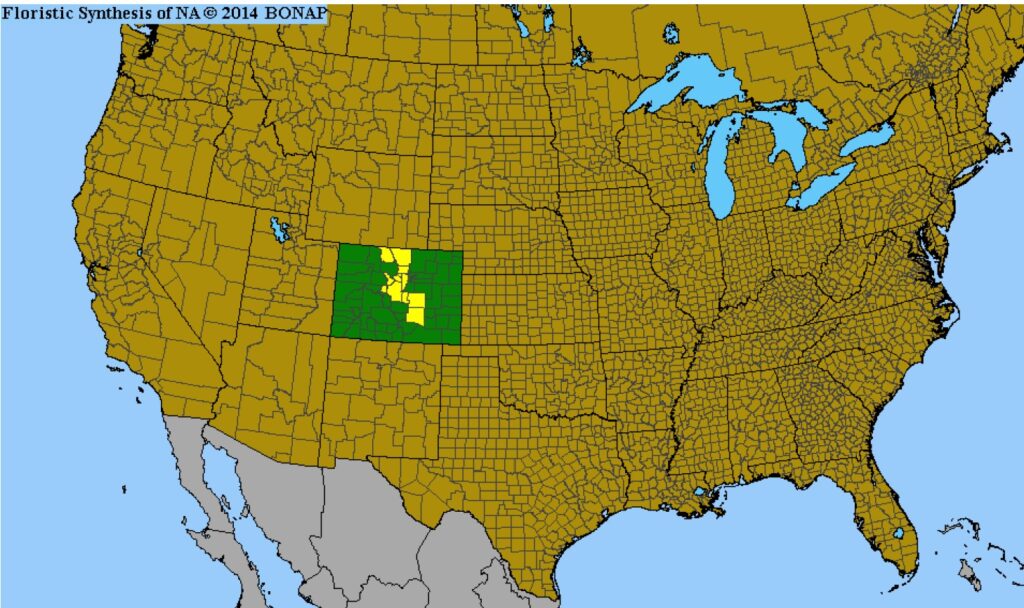

As you can see from the distribution map of Aquilegia saximontana, it is found entirely inside the boundaries of Colorado. Moreover, it is practically restricted to the Front Range from Rocky Mountain National Park to Pikes Peak which means to say that virtually its whole range is visible from Denver on a clear day. Columbines being columbines, the plant possesses a certain extra panache on a generic level, but the specific epithet “saximontana” translates (liberally perhaps) as “Rocky Mountain”. How appropriate to have a plant endemic to our vicinity, an adorable miniature alpine moreover, whose Latin Name recapitulates, as it were, our Chapter’s own epithet.

As with most everything on the planet, the layers of history and associations keep piling on! It just so happens that this columbine is responsible for the beginnings of our chapter’s budget, quite literally. The first meeting of RMC took place in October of 1976 (a date with its own associations) in the University Memorial Center at the University of Colorado. As I recall there were perhaps 30 or so people in attendance (most of whom we never saw again incidentally) as well as a number who HAVE shown up again including Allan Taylor, who procured the room for us to meet in. Paul Maslin, who became the first president of our club, chaired the meeting. Roy Davidson, a great Seattle rock gardener who was on the board of NARGS, gave a short and very memorable speech that helped kick things off. The highlight of the meeting, however, was undoubtedly Homer Hill, a wonderful nurseryman from Wheatridge/Arvada/Golden (it’s complicated). Homer brought a number of flats of Aquilegia saximontana to share. He had been growing our rare state endemic for years to sell at DBG plant sales. Homer had built up enough seed stock that he grew thousands of them in 1976, imagining our BiCentennial would provide a great marketing opportunity for selling such a cute little plant. Alas, I don’t think he timed things quite right, and he was left with quite a large number of flats, so sharing a few was a no-brainer. Those in attendance all scarfed a pot up to themselves, but there were several flats left. What to do? Roy chimed in “our Northwest Chapter members would LOVE to purchase these and I’ll make sure the profits come back to your chapter”, which is exactly what happened.

I don’t recall precisely how much came back. I’m thinking a few hundred dollars? But somehow I find it charming that on our Nation’s bicentennial, at our first meeting, the plant that was to become the Chapter’s avatar helped kick off our finances! But the history (and mystery) does not end here, by any means. Things get much much older and more intriguing…

But before we take this little columbine on its next thematic voyage, let’s spend a minute or two admiring and marveling, really, at what a delightful plant it is. Our Colorado alpine columbine is utterly distinct. There are perhaps a dozen species of miniature columbines scattered around the Northern Hemisphere, many of them spectacular in bloom and foliage. I adore the European miniatures: especially Aquilegia bertollonii which is to Aquilegia alpina much as saximontana is to caerulea, which is to say, a wonderful diminution in size of a taxon that grows sympatrically. Aquilegia discolor is another great tiny European I have grown, slightly different in form, and just as petite as our local gem.

Most of us eventually grow Aquilegia flabellata v. nana supposedly from Japan (and with a perplexed nomenclature)—an outstanding and showy and rather easily grown miniature. But the real show stoppers are found in nearby states: Aquilegia scopulorum, largely restricted to Utah and Nevada, has been lumped with Aquilegia caerulea by myopic botanists, but must surely represent a distinct taxon that many owe its genes to Aquilegia jonesii more than to our state flower. And Aquilegia jonesii should really get the prize for miniature gem of the genus: anyone whose seen mounds of this in full bloom in Wyoming or Montana would surely agree.

at Betty Ford Alpine Gardens trough

But what about our little waif? How can it compare to all these glorious wonders I’ve just mentioned? Shouldn’t we be embarrassed to have championed such a shy little thing when there’s honking A. jonesii in the next state? Well, our Avatar does have a few redeeming features.

Douglas County, Colorado garden

When Pat Hayward worked at Little Valley Wholesale nursery, she was surprised at how quickly Aquilegia saximontana would sell out when they’d built up a stock of it: she explained the phenomenon with a scientific scale she’d made up called “Cuteness Quotient”: you know, the measure we use when looking at little infants, kittens, puppy dogs and (Heaven Help me) little rabbits. They are just irresistible—even to a rabbit hater like me. I find little bunnies in my lawn all the time, and alas my first impulse is (alas) to go “how CUTE” rather than reach for Elmer Fudd’s shotgun which is what I OUGHT to do.

It doesn’t get any cuter than Aquilegia saximontana with those distinctive nodding quaintly shaped blossoms that somehow suggest doll houses, Dutch clogs, tiny birds and all sorts of pleasant things. And unlike most of the other American miniatures, Aquilegia saximontana is incredibly adaptable in both the rock garden and troughs. I have plants that have persisted a decade, and they have a habit of seeding about. And unlike other columbines, it branches and continues blooming for weeks, even months after others are done!

What really has inspired me to write this article is another fateful coincidence: the first herbarium specimen ever made of Aquilegia saximontana was collected in July of 1820, exactly two hundred years (and a few weeks from the time you get this bulletin.) And we are fortunate that this specimen has been preserved at New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx: this is an image of that very specimen:

There are many things that come to mind as I look at this plant, collected on Edwin James remarkable ascent of Pikes Peak on the Stephen Long Expedition. He and his few companions practically ran up the mountain. They took two days, essentially one and a half to climb it from the base, and half a day to descend. He gathered quite a few specimens of various plants on his way up the mountain and penned one of the most eloquent tributes to the alpine ever written afterwards, which I shall append as an afterword to this article.

I am surprised at what a wonderful specimen he managed to collect, press, and transport on foot and horseback for over 1000 miles. And it has sat quietly first at Columbia University’s herbarium where it was received by John Torrey and eventually transferred to the Bronx.

The great mystery to ME is why did John Torrey not give it a name? The answer is pretty obvious: this great botanist who DID name a great many plants from this expedition over the course of a few decades was obviously overwhelmed with so many novelties coming to him from all over North America, this simply slipped through the cracks. Despite the fact that this plant is utterly distinct from James’ Aquilegia coerulea, despite that this specimen is absolutely perfect and shows all the distinguishing characters that almost ANYONE could have used to describe it as a new species, despite all these things the specimen slumbered unmolested forever. I wonder what Torrey might have named it if he had fixated on it for a moment: perhaps Aquilegia jamesii Torr.? He did name quite a few plants after our first botanist after all!

But the plant was not to acquire its wonderful epithet for the better part of a century before the redoubtable Swede, Per Axel Rydberg gave the species its recognized name. Rydberg’s Colorado Flora, the first of four comprehensive floras of our state, was published in 1906 by the “Agricultural Station” at Colorado State University in Fort Collins: I have relished reading and rereading this amazing Flora for the better part of seven decades. His description of Aquilegia saximontana lists many localities mostly in the northern Front Range, none of them appear to be James collection which Rydberg may not have even seen. As an aside, Rydberg lists Phyllodoce empetriformis as growing on Grizzly Gulch, another mystery we must solve!

Several years ago I realized the bicentennial of the Long Expedition was on the horizon and I began reading James’ monumental “Account of an Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains”, first published in 1823 and continuously in print since then. I was worried that this expedition wouldn’t get much attention, trumped, as it were, by Lewis and Clark which got no end of fanfare since it was the first.

The Long Expedition may have come in second, and may be best known for dubbing the Great Plains “the Great American Desert”, which turned out to be a bit of an overstatement. It could be argued that far more in the way of geological, botanical and ethnographic data was collected by the second expedition than there was on the first. And let’s not even begin to talk about poor Zebulon.

Sadly, precious little has shown up in the media about this Expedition, and my worst fears seemed to play out with a few notable exceptions: Mike Kintgen and Jen Toevs have written some outstanding articles about the botany of the Long Expedition that are being published in this year’s “Aquilegia“, the publication of the Colorado Native Plant Society. The Betty Ford Gardens is highlighting five great botanists and explorers in Colorado in their current outdoor Interpretive panels, including Edwin James which will be staged through this summer. And the Rocky Mountain Society for Botanical Artists (https://rmsbartists.blogspot.com/p/about-us.html) is planning a display of some of the key plants collected on the Long Expedition to be staged in the gallery of the Garden of the Gods visitor center in Colorado Springs. This exhibition will rotate later in the year to the Betty Ford Garden visitor center.

Come to think of it, Aquilegia saximontana is notably shy in its demeanor. Unlike brash Pike or John Fremont, the ultimate performer, the scientists of the Long Expedition were long on accomplishment, and notably modest in their marketing. Edwin James led a rich and extraordinary life as a doctor, farmer and family man. He was also a conservationist before the concept even was invented, long before Muir. Edwin was a champion of American Native People. His farm was a major station on the Underground Railroad. His narrative of John Tanner is the earliest one of the greatest anthropological studies of Ojibway life. Despite writing two classics of Americana, James was a modest, unassuming man. I believe he deserves to be recognized as a giant in American intellectual history. And he was the first scientist to collect two of our loveliest columbines after all.

(extract from James’ Account below):